The Big Picture

The False Promise of Tariffs

Supporters of US President Donald Trump’s protectionist policies claim that tariffs will boost government revenue, fuel job creation, and revive American manufacturing after decades of globalization. In fact, Trump’s tariffs are more likely to raise consumer prices, weaken innovation, and undermine US competitiveness.

LONDON – In this era of growing protectionism, defending globalization can feel like a losing proposition. But rather than retreat from the debate, it is more urgent than ever to spell out the costs of a trade war, which threatens to accelerate the fragmentation of the global economy because it is really a war on trade itself. To challenge the logic behind the US administration’s protectionist agenda effectively, we must first understand it in clear and concrete terms.

The Trump administration’s tariff regime stands on four arguments. The first is that tariffs are a tool to boost government revenue – specifically, to help reduce the United States’ budget deficit, which many economists view as unsustainable. The Congressional Budget Office expects the federal deficit, currently at 6.4% of GDP, to remain above 6% through 2035 – notably higher than the 50-year average of 3.8%.

High deficits could limit the US government’s ability to sustain key entitlement programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. To prevent that outcome, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has vowed to reduce the fiscal deficit to 3% of GDP by 2028, using tariff revenues as a primary tool.

By imposing tariffs, the argument goes, the US government would generate revenue from imported goods that are currently exempt from federal taxes. The US government also misses out on income and corporate tax revenue that would have been collected if those same goods and services were produced in the US. In theory, tariffs would offset these losses.

The second argument in favor of tariffs focuses on reciprocity. Advocates contend that while US exports are often subject to high tariffs and taxes, imported goods face few, if any, barriers when entering the US. Thus, the Trump administration is fully justified in imposing equivalent tariffs to level the playing field for American producers.

Third, supporters argue that tariffs will protect domestic industries and help restore America’s manufacturing base, which has been hollowed out by decades of free-trade agreements that shifted production to lower-cost countries like Mexico, India, and China. By incentivizing local manufacturing, tariffs will fuel reindustrialization and job growth.

Tariffs are also often portrayed as a means of rebalancing the economy and redistributing the fruits of globalization, which have disproportionately benefited capital over labor. According to this view, tariffs would help restore the living standards of American workers, who have endured decades of stagnant or declining real wages.

But the case for tariffs goes beyond economic rebalancing and job creation. The US, tariff advocates argue, has become dangerously dependent on fragile and unreliable global supply chains. Relying on other countries – including ideological and geopolitical adversaries – for critical goods like semiconductors, food, and pharmaceuticals poses a serious national-security risk. Tariffs, in their view, are not merely about competitiveness but also about resilience and sovereignty.

Of course, these arguments largely disregard David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage, which holds that countries should produce the goods and services they are best equipped to produce. They also diverge from today’s economic realities in several important ways.

Consider, for example, the claim that tariffs would boost government revenues. While that may be true to some extent, tariffs also increase the cost of imported goods, placing a disproportionate burden on lower-income households with limited purchasing power. In effect, they will harm the working- and middle-class Americans they aim to protect.

Moreover, the government may collect less revenue than expected if consumers avoid imports and shift to US-made goods. Notably, such an outcome – one that tariff proponents claim to seek – would undercut the case for tariffs as a reliable source of federal revenue.

Then there’s the issue of reciprocity. Trump’s tariffs have already triggered tit-for-tat retaliation and escalation, most notably with China, which ran a trade surplus of nearly $300 billion with the US in 2024. Beyond driving up prices, these conflicts will likely limit Americans’ access to foreign-made goods, reducing consumer choice. As Amazon CEO Andy Jassy recently noted, many vendors will simply pass the added costs on to US consumers.

Meanwhile, using tariffs to protect US manufacturing requires enormous government subsidies to rebuild and support uncompetitive domestic industries. The risk is that shielding American companies from global competition will undermine their incentive to innovate and evolve, ultimately weakening long-term US competitiveness. This approach also underestimates the disruptive impact of emerging technologies like AI, which are poised to reduce demand for human labor.

Twentieth-century economic history offers a cautionary tale. The 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which imposed tariffs on tens of thousands of imports to the US, is widely believed to have worsened the Great Depression. By stifling trade and slowing economic growth, it significantly delayed America’s recovery and contributed to the global instability that preceded World War II.

Amid the ongoing debate over the merits and drawbacks of tariffs, one thing is clear: A return to the global economic model of the past 50 years is neither economically viable nor politically realistic. While identifying and dismantling the claims made by tariff advocates is a useful first step, supporters of global markets and free trade must go further and articulate a credible alternative to Trump’s protectionist agenda.

The Global South Will Pay for Trump’s Trade War

Donald Trump’s tariffs have disrupted supply chains, roiled global markets, and escalated the trade war between the United States and China. While US consumers brace for higher prices, low- and middle-income countries will bear the brunt of the crisis, from currency depreciation to rising borrowing costs.

NEW DELHI – US President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs have unleashed economic chaos, roiling stock and bond markets and triggering panic around the world, especially in lower-income countries that rely heavily on exports to the United States. The result could be an entirely manufactured global recession, with the developing world bearing the brunt.

The brief calm in financial markets following Trump’s abrupt announcement of a 90-day “pause” on most of his “reciprocal” tariffs – excluding those on Chinese imports, which he raised to 145% – has proven premature. While some billionaires and loyalists may have made a killing by correctly interpreting Trump’s social media posts ahead of his sudden policy reversal, the disruptions to global trade and finance caused by his tariffs continue to pose serious risks.

Moreover, despite the pause on some tariffs, a universal 10% tariff on all US imports remains in effect, along with sector-specific tariffs of 25% on steel, aluminum, automobiles, and auto parts. There are new exemptions for smartphones, computers, and other electronic devices, even as Trump has also threatened new duties on pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, copper, and lumber. Taken together, these measures will reduce the availability of imported goods, raise prices for US consumers, and impose steep costs on exporting countries.

But ultimately, the tariffs imposed on each country will depend on future negotiations, where the US is expected to play hardball. Trump has already made clear his disdain for foreign leaders, boasting that many were “kissing my ass” and willing to “do anything” to reverse the tariffs. As a result, the final scope of Trump’s tariffs remains uncertain.

Most critically, Trump’s latest tariff hike on Chinese imports all but ensures that the Sino-American trade war will continue to escalate. The increase to 145% is largely symbolic – a tit-for-tat move after China raised its own tariffs – since the previous 104% rate had already made most Chinese imports commercially unviable. In effect, the administration has signaled its intent to shut down trade with China.

The implications for US consumers and domestic producers that rely on Chinese inputs are profound. Trump’s open distrust of goods from Chinese-owned factories – even when routed through third countries – has forced governments hoping to maintain access to the US market to scramble for alternative sourcing and production options. The mere expectation of such shifts has already severely disrupted global supply chains.

Uncertainty has always been a major deterrent to economic activity, and the unpredictability of the Trump administration’s policies – marked by erratic decision-making, sudden reversals, and on-again, off-again announcements – has made future developments nearly impossible to anticipate using standard risk models. Trump’s preference for shock-and-awe tactics, reminiscent of other “strongmen” like Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, compounds the problem.

Rising uncertainty will inevitably discourage investment, as businesses shelve new projects and postpone planned expansions while waiting to see how events unfold. The subsequent slowdown could weigh heavily on US growth and employment, with consequences that extend far beyond the direct economic impact of Trump’s tariffs.

Worse still, the US cannot win its trade war with China. The Chinese government clearly knows this and is playing the long game. At any moment, the two superpowers’ economic war of attrition could spiral into a major financial crisis or even a military confrontation.

The alarm bells are already ringing. The falloff in demand for US Treasury bills, long considered the world’s safest asset, signals diminishing confidence in America’s economic leadership. Moreover, the simultaneous drop in US stocks, bonds, and the dollar points to growing doubts about US Treasuries’ ability to serve as the global benchmark for asset prices, even as they remain the preferred vehicle for high-volume financial transactions.

As with previous self-inflicted economic crises, the US economy will undoubtedly suffer, but the heaviest burden will fall on the developing world. Canceled or delayed export orders are already undermining production and fueling unemployment. Meanwhile, financial volatility is threatening economic stability long before the full impact of Trump’s tariffs can be felt.

These developments are already reflected in the yield spreads on developing countries’ sovereign bonds, particularly those of lower- and middle-income economies. In the month leading up to April 9, emerging-market sovereign dollar debt values fell by an average of 2.9%, while average yields rose to 7.4%. The sovereign bonds of debt-stressed countries like the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Gabon, and Zambia dropped by more than 10%.

Unfortunately, developing countries are all too familiar with this kind of financial and economic turmoil. For decades, many have been trapped in a cycle of currency depreciation, rising borrowing costs, strained public finances, forced spending cuts, and domestic market instability that constrained investment and private-sector activity.

The lessons for developing economies are clear. Not only is globalized trade being upended, but financial globalization is bound to become even less appealing to countries seeking stable, long-term financing to support their development goals.

Trump is determined to dismantle the global economic order, which in his view allows other countries to take advantage of the US. In response, many developing economies will likely begin to reconsider their participation in – and subordination to – an unequal system that no longer serves their interests. But the road ahead will remain perilous until a credible alternative takes shape.

Trump’s Tariffs and the Will to Power

Donald Trump views tariffs as much more than a policy. While they will make life materially worse for people around the world – not least Americans – what matters to him is the spectacle of a heroic leader demonstrating his capacity to induce shock and awe.

NEW YORK – In the days since US President Donald Trump unleashed his tariff tsunami on the world, economists, investors, and business leaders have almost universally questioned its rationality. As a policy matter, they are right to be scratching their heads. But Trump’s tariffs are not simply about policy. They are of a piece with the animating features of his MAGA (“Make America Great Again”) movement: contempt for science and the rule of law, persistent lying, and a propensity for irrational theorizing.

We have witnessed this embrace of unreason before, accompanied by similarly grandiose assertions of power. Hitler’s well-known fascination with Theosophy, Gnosticism, and eugenics was not an isolated phenomenon. During the 1930s, psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s idea of self-growth or “individuation” was viewed by many (including Jung) to be the special destiny of the Aryan race. The well-known Eranos gatherings during this period, which included esteemed scholars such as Mircea Eliade (who publicly supported Romania’s fascist Iron Guard), Henry Corbin, and Gershom Scholem, have been shadowed (not entirely fairly) by the taint of anti-Enlightenment politics.

For Trump, tariffs are about much more than a change of economic policy. They are part of a toolkit for political and cultural transformation. April 2 was “Liberation Day.” Trump sees himself as single-handedly and fundamentally altering the global order by a Herculean act of sheer will. To be sure, Trump’s tariffs are likely to make life materially worse for people around the world – not least Americans. But the particulars matter less than the heroic spectacle itself, the leader’s demonstration of MAGA’s capacity to rivet our attention by arousing shock and awe. To borrow the Silicon Valley mantra (which echoes in Gnostic reveries), one must move fast and break things to release creative energy, including the spirit of the homeland. Mystical leaders liberate crippled instincts from conventional cultural shackles – like the “wholly incongruous Christianity” that, as Jung put it, had been “grafted upon the stumps” of the Aryan spirit.

Who else could mobilize such transformative forces but the great leader – the one who, as Nietzsche put it, carries chaos within to give birth to “a dancing star”? That’s the MAGA pitch. The test follows: Are you willing to accept the pain that ensues? This is less an implementation of policy than a collective initiation rite, or a massive psyop. As Soviet propagandists understood, inducing friends and foes alike to repeat obvious falsehoods is a reliable test of power.

So is declaring a state of emergency, as Trump did in order to justify his tariffs. Declarations of this sort embody a claim to ultimate sovereignty. As the Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt wrote, the executive decision to initiate a “state of exception” determines what sovereignty means in practice. It is a self-fulfilling act: declaring an emergency is the emergency. It is one way in which the rule of law ends.

A state of emergency addresses both how the nation will survive and who will survive. That is why Schmitt separates people into friends and enemies. For example, Elon Musk’s definition of friends can be inferred from the companies he owns, such as X.AI, Neuralink, and SpaceX. On this reading, Musk’s friends are the evolving vanguard of humankind: those who are the most AI-informed, even cyber-enhanced, and perhaps destined to colonize Mars.

Enemies, by contrast, have no claim either to society’s concern or its resources. In this vein, Trump focuses above all on “illegal aliens,” whom he routinely describes as “vermin” and “animals.” By defining any “de-nationalized” class of “others” as a discrete sub-species, Trump places them beyond law’s safeguards.

Trump’s tariffs reflect the MAGA movement’s broader anti-Enlightenment impulses. He may claim to be concerned with “rebalancing” global trade, restoring America’s manufacturing industries, and raising revenue. But, more fundamentally, his tariffs are an expression of the will to power – spiked with a jolt of metaphysics.

The embrace of irrationalism in Europe during the 1930s facilitated the rise of fascism. Today’s mythic narratives – from AI-enhanced “evolving” consciousness to Russian Cosmism and Vladimir Putin’s “Noöcracy” (which lays claim to a species of Russian nationalism likewise rooted in man’s destiny to evolve, and which shares Musk’s desire to colonize other worlds) – serve a comparable function: totalizing power.

What Putin’s Noöcracy has in common with billionaires like Musk and the MAGA movement (including its New Age “MAHA” (Make America Healthy Again) contingent led by US Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.) is the cult of personality that lies at their center. Only Putin can serve as the Russian people’s savior. Only Musk can take his acolytes to the next level of evolving consciousness. Only Trump can make America great again by breaking the old order and ushering in the new. Submission to the leader is what makes it all happen.

Yes, the populist “spirit of the people” faction and Musk’s libertarian/Silicon Valley faction embody contradictory interests and goals. The intense rivalry and jockeying for influence within MAGA between Steve Bannon (for the populists) and Musk is the tip of the iceberg.

But this division has so far been modulated, and arguably exploited, by Trump and his loyalists. After all, it is the leader who exclusively embodies the mystical, creative-destructive spirit whose power can guide the nation to its destiny. Whether that destiny empowers the masses (as Bannon insists) or billionaire libertarians like Musk and Peter Thiel remains to be seen. It cannot be both.

For now, as Trump’s tariffs make clear, sound trade policy takes a backseat to both sides’ goal: the consolidation of autocracy. “Liberation Day” has put everyone who has thrown in their lot with MAGA on notice that without Trump at its center the movement that has promised them so much will collapse.

Flipping the Trump Script

The world order needed renewal before US President Donald Trump’s "Liberation Day," and it needs it even more now. As misguided as his trade warfare is, it does not necessarily have to lead to collapse, as in 1929, or to another Pyrrhic victory for the managerial class, as happened after 2008.

CAMBRIDGE – For the past week, commentators have almost universally framed US President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” as an economic Armageddon. So have investors; reeling financial markets have resulted in a 90-day pause on most of the new tariffs, with the important exception of those imposed on China.

But we have fallen into a narrative trap if our only choice is between Liberation and Armageddon. Both narratives assume “endism”: one era – and all its characters, ideas, and institutions – will be replaced by another. For Trumpians, this is a heroic story about a savior, unrestrained by old norms, who will deliver American greatness. For critics, it is a tragic story of loss, dominated by malevolent characters pursuing their own private interests over the common good.

But endism is not the only way to frame the current crisis. There could also be an opportunity to renew and reform the world order, but only if we change the script. Liberation Day was a shock, but what kind? Some shocks lead to collapse, others cause malaise but do not bring the system down, and still others lead to renewal. Right now, the collapse narrative is dominant. But that could change.

Many are likening the Trump shock to the anti-globalism that underpinned the Great Depression. But the parallel to the 1930s should not be pressed too hard. The global system was more fragile then than it is now, with far fewer instruments to prevent disaster. After World War I, the United States emerged as the global banker, but this status rested on an overheated, under-regulated, brittle domestic banking system. When the 1929 financial crisis came, it unleashed a bankruptcy wave that sent unemployment rocketing toward 9%. Then protectionists piled on and turned a crash into a depression.

After the Tariff Act of 1930, introduced by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willis Hawley, and reluctantly signed by President Herbert Hoover, jacked up US tariffs, America’s trading partners reciprocated, and markets tanked. The multilateral trading system of the era, overseen by a feeble League of Nations in Geneva, was finished. Within two years, US unemployment topped 23%.

Ever since, Smoot-Hawley has become a watchword for economic idiocy, and Trump’s critics cannot resist invoking it. But doing so ignores other crises that might point to alternative narratives. It also misses a crucial irony: one outcome of the Great Depression was the establishment of buffers and guardrails to prevent another collapse. Those instruments, burnished and updated through many financial upheavals since 1945, did indeed create a more resilient system. Moreover, what happened in finance also applied in global health, security, and cultural awareness.

While pointing to the Great Depression favors calamity narratives, another storyline is almost as dangerous, because it usually kicks in only after the voices of doom have gone hoarse. This is the “muddling through” narrative, which tends to be most favored by crisis managers, who just want to get back to business as usual. One can already see it taking shape as trading partners line up at the White House or Mar-a-Lago to strike a deal. Many will offer to pay tribute to the scowling aggressor to prevent escalation, offering concessions like the creation of a “fentanyl czar” or a promise to buy Iowa corn. We could hear the muddlers’ collective sigh of relief on April 9, when Trump paused Liberation Day.

Muddling through is what happened during the 2008 financial crisis. At first, alarmists warned of a repeat of 1929. But the global managerial class had the tools to stave off a collapse. The situation became what one political scientist called a “status quo crisis”: severe enough to impose a toll on millions of homeowners, Greeks, and Ukrainians, but not to force systemic reform. In the event, the managerial class relied on cheap credit (quantitative easing) and cheap carbon (thanks to shale energy and liquefied natural gas) to fuel a recovery, the price of which has now come due.

Muddling through looks effective at first (recall all the executive bonuses handed out in 2009), but fails to address the root of the problem. What we needed after 2008 was a course correction in globalization – a renewal of the global compact to make it fairer and more inclusive. Obviously, that did not happen.

Muddling through worked until 2016, when Brexit, Trump’s first election, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s weaponization of energy interdependence, and pandemic-era “vaccine nationalism” left Davos Man no muddle room. Globalists’ legitimacy has been draining away ever since.

Are we repeating century-old errors, nudging a crisis into a collapse? Are we about to muddle through again? Or could this moment be a renewal, spurred by recognition that the earlier model of globalization was not working for enough people?

The renewal narrative has been crowded out, but history is full of such moments. World War II led to the dismantling of empires and the making of a new world order. The collapse of the Soviet Union spurred democratization in many parts of the world, new human-rights norms, and efforts (limited as they were) to take the environment and climate change seriously.

The world order was in trouble well before the rise of Trump. Nuclear proliferation was back, inequality was rising, pledges to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions were in retreat, and the global trading system was adrift. The Doha Round of trade negotiations ended in ignominy, and the World Trade Organization’s charter became obsolete. If we limit ourselves to patching up this flawed interdependence, we will join the post-2008 muddlers.

The world needed renewal before Liberation Day, and it needs it even more now. As misguided as Trump’s trade warfare is, it does not have to lead to collapse or another Pyrrhic victory for the managerial class. The path to renewal begins with more creative thinking. We should focus on the globalization we need. Attempting to rescue status quo globalization or to accept the White House’s caricature of American supremacy are not the only options. By favoring calamity over possibility, they are both dead ends.

Trump, Tariffs, and the Fate of the Dollar

Donald Trump’s attempt to reindustrialize the US economy by eliminating trade deficits will undoubtedly cause pain and disruption on a massive scale. But it is important to remember that both major US political parties have abandoned free trade in pursuit of similar goals.

PROVIDENCE – With the Trump administration imposing “insane” tariffs on the rest of the world, many commentators are worried about the problem of “sane-washing”: imputing cogent rationales to policies that have none. Such naive punditry, they argue, distracts from the grift that is unfolding before our eyes. The Trump family’s moves into the crypto sphere – where its meme coins serve as an open invitation for bribes – certainly support this interpretation. But is this the only conclusion to draw, or could something else be going on?

Consider an alternative explanation.

The US project of promoting global free trade had already been abandoned by the time of the 2016 election, when both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton campaigned against the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Trump then imposed tariffs on goods from China and other countries, and many of these were maintained or extended under President Joe Biden. One of Biden’s signature policies, the Inflation Reduction Act, was an attempt to promote US reindustrialization in green sectors, which, in addition to being protected by Trump’s tariffs, would be subsidized. Trump’s latest wave of tariffs is also supposed to drive reindustrialization, albeit of a more carbon-intensive variety. Thus, free trade seems to be off the menu for both Republicans and Democrats.

The reason for this bipartisan embrace of protectionist policies concerns the global role of the dollar in promoting structural trade imbalances. As John Maynard Keynes recognized back in 1944, all countries, left to their own devices, would rather be net exporters than net importers. Today’s net exporters in the European Union, Asia, and the Gulf earn dollars that their own economies cannot absorb, because that would raise domestic wages and prices, undercutting their competitiveness. The earned dollars are liabilities for local banks, and the easiest way to turn them into assets is to buy US government debt, effectively handing the cash back to the United States so that it can continue to buy exports.

Thus, for the past 40 years, the US has imported pretty much anything it wants by issuing digital IOUs that pay 2% interest without ever being redeemed, because T-bills are the same exporters’ go-to savings vehicle. This means, among other things, that the US has no current-account constraint.

Why would the US want to end this seemingly magical state of affairs? Because, as Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis argue, defying current-account constraints does in fact carry long-term costs. Countries that are net exporters build up huge surpluses at the price of undercutting domestic investment and local wages, which depresses their economies, while the US “benefits” from unlimited cheap foreign goods, but at the price of hollowing out its own industrial capacity. In 1975, the three largest employers in the US were the Exxon corporation, General Motors, and Ford; in 2025, the biggest employers are Walmart, Amazon, and Home Depot. The first group made tradable goods, while the latter companies by and large sell imports domestically.

Given these long-term effects, leading figures in both US parties have come to regard the dollar’s “exorbitant privilege” as an exorbitant burden. Both parties want to “rebalance” the US economy by promoting domestic production, which entails a forced adjustment on foreign exporters to curtail their demand for dollars.

Why don’t they just come out and say this? Probably because talk of “being ripped off” by other countries is more compelling to the base than arguments about the finer points of trade policy. Moreover, the fact that the Trump administration lacks a comprehensive plan to rebalance the global order doesn’t mean that such a reordering is not already happening.

After all, Germany’s export engine was sputtering even before the pandemic. Its recent loosening of the “debt brake” (a constitutional cap on structural deficits) and embrace of investment suggests that a rebalancing toward domestic consumption is already underway. The Trump-driven surge in EU defense spending will add more momentum to this trend, and the prospect of a more consumption-driven euro area will give global investors a viable alternative to the dollar.

As for China, it seems to have realized that flooding the rest of the world with green exports (electric vehicles, solar panels, and so forth) has its limits. It has already diversified away from the US market, and this has increased the need for greater domestic consumption. Meanwhile, the rest of export-driven Asia seems keen to set up shop in the US to retain market access.

Such a rebalanced world would need fewer dollars. Ending the current system will be massively disruptive, no doubt, and the prospect of US reindustrialization may prove illusory. But it is important to remember that both parties see it as necessary. The rebalancing began before Trump arrived on the scene, and is being driven by forces that may outlast him.

Who Will Drive the Post-American Global Economy?

For any country that depends on international trade and markets, it is now obvious that even if the United States can be persuaded to rein in its trade-war policies, new trading arrangements will be necessary. There has never been a better time to pursue new, coordinated strategies to boost domestic demand.

LONDON – Since the US presidential election last year, I have been commenting regularly on various aspects of Donald Trump’s agenda and what it might mean for America, financial markets, and the rest of the world. There has been no shortage of chaos, but that was largely expected, given the president’s ham-handed, erratic “method” of policymaking.

As I noted in February, and again in March, other economies may respond to Trump’s aggression by boosting their own domestic demand and reducing their dependency on US consumers and financial markets. If there is a positive spin to the current mess, it is that Europeans and the Chinese have already started to pursue such changes. Germany is loosening its “debt brake” and allowing for sorely needed investment, and China is said to be studying its options for stimulating domestic consumption.

For any country that depends on international trade and markets, it is abundantly obvious that, even if the United States can be persuaded to rein in its trade-war policies, new trading arrangements will be necessary. Many are already seeking ways to increase trade among themselves and to forge new agreements to lower non-tariff barriers in the rapidly growing services trade.

As a bloc, the rest of the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom) is nearly as large as the US. Add the other participants in UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s “coalition of the willing,” and America’s erstwhile allies could offset much of the damage that Trump has inflicted. By the same token, if China could refashion its Belt and Road Initiative in close coordination with India and other larger emerging economies, that might prove transformational.

Such moves would mitigate the effects of US tariff policies and threats. But they will not be easy to pull off; if they were, they already would have happened. Today’s trading and financial arrangements reflect a variety of political, cultural, and historical factors, and the Trump administration will try to derail any changes to the status quo that could benefit China.

What matters, then, is precisely how other large economies go about stimulating domestic demand, mobilizing investment, and forging new trade ties. At a recent conference on “globalization and geo-economic fragmentation,” hosted by the think tank Bruegel and the Dutch central bank, I was reminded just how skewed global GDP growth has been since the turn of the century. A simple analysis of annual nominal GDP figures from 2000 to 2024 shows that the US, China, the eurozone, and India collectively contributed nearly 70% of all growth, with the US and China accounting for almost 50% between them.

This finding further underscores the fact that US tariff threats must be met with higher domestic demand elsewhere. But here is a reality check: The only other country that could singlehandedly boost its demand and imports by enough to compensate for America’s declining share of the global economy is China.

But what if China isn’t operating singlehandedly? As we have seen, Europeans are already taking steps to increase investment and defense spending in ways that will benefit both the EU economy and others, like the UK. And, of course, India’s economy has been growing faster than many others in recent years, suggesting that it could have some scope to pursue more domestic stimulus. What if all these other economies were coordinating their own policies?

Such coordination probably might not have the same global impact as the 2009 London G20 agreement, which introduced wide-ranging global reforms and new institutions to address the causes of the global financial crisis and its fallout. But if these countries signaled to the rest of the world that they were engaged in some kind of consultation to harmonize their economic policies and advance shared objectives, that could have quite a positive impact.

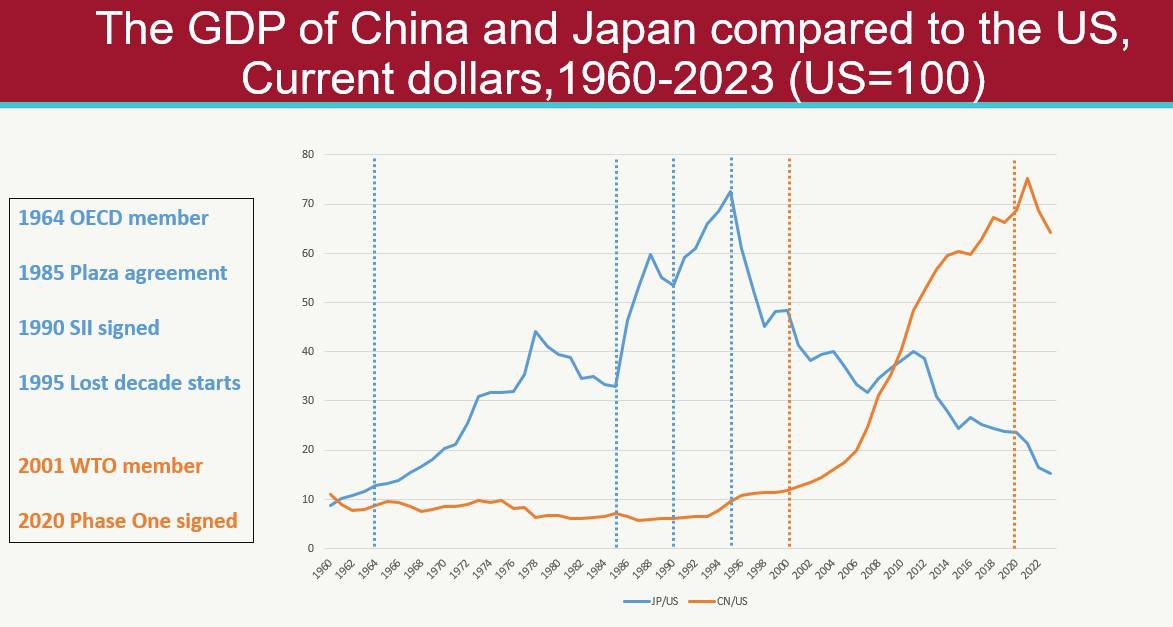

Finally, something else from the Bruegel conference has been nagging away at me. It was a chart (see below), presented by Bruegel Senior Fellow André Sapir, highlighting the similarities between Japan’s rise, when its GDP grew to around 70% that of the US in the 1990s, and China’s today. Then as now, the great fear in America was that it would be “surpassed.” But what does America really want? Does it want to be able to say that it is the largest economy in nominal terms, or does it want to provide wealth and prosperity for its citizens?

These are not necessarily the same thing. What the current US administration fails to understand is that other countries’ growth and development can make Americans themselves even wealthier. Perhaps, someday, Americans will elect leaders who can comprehend this basic economic insight. For now, though, they seem destined for many years of turmoil and persistent uncertainty.

Will Trump Unite China and Europe?

By making trade with the United States more expensive, Donald Trump created a powerful incentive for closer ties between China and the European Union. Notwithstanding their conflicting positions on issues like the war in Ukraine, the world’s second- and third-largest economies now have common ground between them.

ROME – With little economic or political rationale, US President Donald Trump has introduced some of the highest tariffs in more than a century, and imposed them on nearly every economy in the world. Then, suddenly, despite his insistence that the tariffs were here to stay, he paused the new “reciprocal” tariffs for all countries except one, keeping in place an across-the-board 10% levy for the rest. For China, Trump added a 50% tariff on top of the two 10% tariff hikes in February and March and the 34% “reciprocal” tariff levied on his “Liberation Day” (which he then increased to 84% by executive order). The result? An effective minimum tariff rate of 145% on all Chinese goods entering the United States (with a temporary reprieve for consumer electronics).

China, which had retaliated with proportional tariffs to the two initial 10% hikes and had hoped for a deal with Trump, has responded to his last two hikes with matching increases, bringing the overall tariff on US imports to 125%.

The Trump administration is betting that the Chinese government cannot withstand the economic losses from a sharp reduction in US trade. Just under 20% of Chinese GDP comes from exports, and around 14.7% of its exports go to the United States – China’s second-largest export market in 2024. A 145% levy on these exports will exact a heavy toll on Chinese firms, workers, and families at a time when China is struggling to re-energize a stalling economy.

But Trump’s bizarre and aggressive launch of his tariffs handed the Chinese government an important political advantage. Unlike economic downturns that can be attributed to domestic policy, Trump’s bluster and indiscriminate, punitive tariffs against small, poor countries like Lesotho, or islands populated only by penguins, will lead most ordinary Chinese to blame economic pain on “US bullying.” The Chinese government repeatedly emphasizes the mutual benefits of trade and that “no one wins” in a trade war. At the same time, it has called for national solidarity. The less reasonably America behaves, the more domestic support the Chinese government will receive.

Moreover, China is not alone. While the Biden administration worked assiduously with its allies to isolate China, Trump has put China and traditional US allies on the same side. For example, he increased tariffs on EU imports by 20%, and the EU, like China, had announced retaliatory tariffs before Trump, facing crashing stock markets and rising Treasury yields, abruptly hit the pause button.

America’s recent focus on China may be seen as an effort to realign Europe and other countries against China. This may work to some extent. Mexico has already offered to match US tariffs on China. But much of the self-inflicted damage to US interests has already been done. Even if the EU successfully negotiates with the US, the tariffs and the tensions over Ukraine and Greenland will have a permanent negative effect on Europeans’ faith in America as a reliable economic partner and strategic ally.

Frustration with the US will not suddenly make Europe an ally of China. The EU has plenty of complaints against China, especially its flood of electric-vehicle (EV) exports and support of Russia in its war against Ukraine. But, by making trade with the US more expensive and unpredictable for everyone, Trump has created a powerful incentive for Europe to deepen ties with the People’s Republic.

Moreover, while Trump has pulled the US out of the Paris climate agreement (again), Europe and China both recognize the need for urgent action against global warming. In addition to leading the world in EV and solar-panel manufacturing, China is also the fastest developer of green-energy technologies and nuclear power – an energy option that has gained renewed interest in Europe.

The Ukraine war and the effects of Chinese exports on European producers are undoubtedly sticky issues; but the need to insure their economies against American chaos may motivate the two sides to compromise. What a deal might look like is hard to say, but there are many options. China could increase its European imports, set limits on its exports to Europe, and allow its currency to appreciate. It could also share technologies to help bolster European industries such as AI, EV batteries, and electric transmission. This would turn Chinese government subsidies in these sectors, which Europeans view as giving China an unfair advantage, into a benefit for European producers and consumers. Europe, for its part, could promote Chinese participation in more global decision-making processes – something that Chinese leaders have long sought.

While China is unlikely to abandon Russia, it has exhibited pragmatism when it comes to Chinese interests. If it wants to show goodwill to the Europeans, it can increase imports of Ukrainian foodstuffs to offset some of the loss of American agricultural imports, support Ukrainian refugees, use its expertise in building large infrastructure projects to help with Ukrainian reconstruction, and prevent Chinese mercenaries from joining Russia.

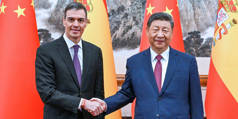

The recent visit of Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez to Beijing, and a planned meeting with EU leaders that Chinese President Xi Jinping will host in July, clearly indicate that the world’s second- and third-largest economies are well aware of the benefits of increased cooperation. If they pursue it successfully, the trade war may not be all bad for China, and what looks like an economic crisis may also be a geopolitical opportunity.

Less than 24 hours after his “retaliatory” tariffs went into effect – sending the US stock and bond markets into a tailspin – US President Donald Trump “paused” them for 90 days, ostensibly to give America’s trading partners a window to strike deals with his administration. Meanwhile, a 10% tariff on imports from all countries remains in effect, along with 25% tariffs on steel, aluminum, automobiles, and auto parts.

Trump’s tariffs cannot possibly achieve their purported – and contradictory – goals of boosting government revenue, fueling job creation, and reviving American manufacturing, notes international economist Dambisa Moyo. Instead, they are likely to “raise consumer prices, weaken innovation, and undermine US competitiveness.”

But while US consumers and domestic producers will suffer mightily, points out Jayati Ghosh of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the developing world will suffer the most, as it grapples with “currency depreciation, rising borrowing costs, strained public finances, forced spending cuts, and domestic market instability.” Trump may well be setting the stage for an “entirely manufactured global recession.”

It does not matter to Trump that his tariffs “are likely to make life materially worse for people around the world – not least Americans,” explains Richard K. Sherwin, Professor Emeritus of Law at New York Law School. “This is less an implementation of policy than a collective initiation rite, or a massive psyop.” The point is the “heroic spectacle, the leader’s demonstration of MAGA’s capacity to rivet our attention by arousing shock and awe,” which is part and parcel to the “consolidation of autocracy.”

Just as Trump’s supporters see his behavior as a “heroic story about a savior” who will “deliver American greatness,” observes Jeremy Adelman, Director of the Global History Lab at the University of Cambridge, critics view it as a “tragic story of loss, dominated by malevolent characters pursuing their own private interests.” But this focus on “endism” crowds out another possibility: that Trump’s tariffs have created an opportunity to “renew and reform” a world order that was “in trouble” well before his rise.

In fact, according to Brown University’s Mark Blyth, a global “reordering” was underway when Trump returned to power, exemplified by German and Chinese moves to rebalance their economies toward domestic consumption. In fact, both major US political parties want to “‘rebalance’ the US economy by promoting domestic production” – a “massively disruptive” shift that would significantly reduce the world’s need for US dollars.

Jim O’Neill, a former chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management and a former UK Treasury minister, thinks there “has never been a better time to pursue new, coordinated strategies to boost domestic demand.” If large economies, such as China and the European Union, engage in “some kind of consultation to harmonize their economic policies and advance shared objectives,” it could have “quite a positive impact.”

This is not farfetched. While “frustration with the US will not suddenly make Europe an ally of China,” notes Northwestern University’s Nancy Qian, Trump has given the world’s second- and third-largest economies a “powerful incentive” to deepen their ties. Though it is “hard to say” what an agreement would look like, the basic premise is that China-EU cooperation would “insure” both against “American chaos.”

What matters, advises Daniel Gros, Director of the Institute for European Policymaking at Bocconi University, is that the rest of the world avoids succumbing to the temptation to retaliate against the US, let alone impose tariffs on their other trading partners. The EU has an important role to play here: by “rally[ing] a coalition of like-minded countries to uphold the open, rules-based global trading system that the US has abandoned,” it should ensure that the damage is limited entirely to the US – a goal which even a “small dose of liberalization for everybody else” would advance.

However the world responds to Trump’s tariffs, writes Shlomo Ben-Ami, Vice President of the Toledo International Center for Peace, it seems clear that Pax Americana – which was “was always based on a broadly beneficial, but primarily self-serving, system of economic, military, and cultural projection” – is coming to an end, and the US is the one destroying it. Given this, all China needs to do is “sit back and watch.”